A (myocardial) bridge too far: CT vs. IVUS in the heart

By Eric Barnes, AuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 8, 2015 — Multidetector-row CT should be considered the noninvasive gold standard when evaluating myocardial bridge abnormalities, owing to its anatomic accuracy. But there are important things CT doesn’t see that intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) does, according to new research from Stanford University.

In a study of 64 patients with clinical symptoms of ischemia who underwent both CT and IVUS, CT’s anatomical assessment was uniformly excellent. However, it missed most septal branches and noncalcified plaque that could present serious risks for patients, reported Dr. Hans-Christoph Becker and colleagues.

Despite these shortcomings, “we had good correlation between CT and IVUS for anatomic assessment,” Becker said. “We can consider CT as the noninvasive gold standard for the detection of myocardial bridges.”

Often benign, sometimes dangerous

Myocardial bridges are the most common coronary anomaly; they present in different ways and incidences depending on what modality is detecting them, Becker said in a June presentation at the International Symposium on Multidetector-Row CT. Generally speaking, they don’t impair blood flow because compression of the vessel usually takes place during systole, whereas the blood is flowing in diastole.

Dr. Hans-Christoph Becker from Stanford University.

“However, in certain circumstances, extended compression beyond the systolic phase may indeed impair blood flow through the affected coronary segment, and may lead to various signs of myocardial ischemia such as recurrent chest pain, conduction abnormalities, or rhythm disorders,” Becker said.

The presence of myocardial bridges is often associated with atherosclerotic lesions, “which are often vulnerable and prone to rupture and, of course, sudden acute events, and this may be another pathological mechanism for clinical presentation of myocardial bridges,” he said. The benign and acute presentations — and transformation of some asymptomatic presentations into acute symptoms — have led some researchers to call the condition a double-edged sword.

“Over the years, the heart may change in a way that there’s ventricular hypertrophy present, as well as diastolic dysfunction and endothelial dysfunction,” Becker said. “All these lead to the fact that blood flow may be altered in a way so that myocardial ischemia may be present during the development of changes within the myocardium.”

The plaque developments in myocardial bridges aren’t completely understood, but they are thought to be related to flow dynamics and wall shear stress, he said. The phenomenon probably explains why plaque forms in front of or behind a myocardial bridge but never within it. And the surrounding epicardial fat mediates factors that may contribute to atherosclerotic plaque formation.

IVUS vs. CT

It is the widely varying presentations and implications of myocardial bridges that make imaging important. Some myocardial bridges barely touch the left ventricle and not the myocardium, while others are completely encased by the myocardium, as evidenced by a thickened layer of myocardium surrounding the coronary artery at CT, Becker said.

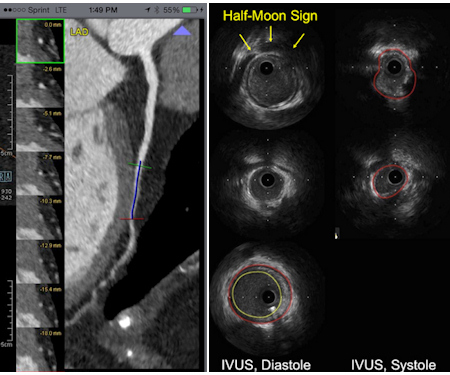

IVUS has its own ways of depicting a myocardial bridge, notably the echolucent half-moon sign, an area surrounding the coronary artery that is translucent and varying in thickness depending on the thickness of the myocardial bridge, he said.

Left, myocardial bridging with encasement of the coronary artery in the myocardium at CT. Right, echolucent half-moon sign in IVUS indicates myocardial bridging. Images courtesy of Dr. Hans-Christoph Becker.

In their retrospective study, Becker and colleagues examined 64 patients (ages 13-72 years) who underwent both coronary CT angiography (CCTA) and IVUS between 2009 and 2014. Their goal was to determine which tool — IVUS or CCTA — was the better imaging modality.

Among the limitations, a five-year study period meant that several different CT scanners, including four different 64-detector-row machines and two 2 x 64-detector scanners, were used over the course of the study, yielding variable image quality, according to Becker.

But IVUS and CT were very well-correlated with regard to vessel encasement seen on CT and the thickness of the halo sign in MR, particularly if there was full encasement at CT. The halo-sign thickness on IVUS tended to be in the range of 0.8 mm.

“Similarly, we found good agreement between the measurements derived from CT and IVUS in terms of the distance from the circumflex to the bridge, as well as the length of the bridge itself, so these two modalities can be compared quite well for the assessment of these measurements,” he said.

CT’s plaque blind spot

Both modalities were proficient at plaque detection, a very important consideration in myocardial bridges. But IVUS was the clear winner, Becker said.

“It turned out that those plaques that are noncalcified in IVUS are not being seen in CT,” he said.

The group reported the following:

Only 75.4% of septal branches in IVUS were also seen in CT.

57.6% of patients had wall thickness greater than 20% in IVUS.

43.8% of patients had mixed plaques at CT.

IVUS is very sensitive for detecting any kind of wall thickness, Becker said. In the coronary arteries, any thickness over 20% is thought to correspond to atherosclerotic plaque burden.

Nearly 60% of patients had atherosclerotic plaque burden, but fewer than half had calcified or mixed plaques of the type that could be seen on CT.

“So, obviously, CT is not a very sensitive tool to detect these noncalcified lesions that are probably also prone to rupture in these patients with myocardial bridges,” Becker said. “Nevertheless, since we have a good correlation between CT and IVUS for the anatomic assessment, one can say that we can consider CT as the noninvasive clinical gold standard for the detection of myocardial bridges.”

These results help elucidate the sensitivity of stress echocardiography in identifying patients with myocardial bridges by means of the specific echo-buckling sign in a larger clinical cohort, because many patients in this population do not undergo imaging beyond echo, he said.

“And this will probably also allow us to look into the outcomes of these patients, and to assess the cost-effectiveness of stress echo as well as CT for workup.”