‘Huge leap’ in prostate cancer testing

By James GallagherHealth and science reporter, BBC News website

20 January 2017From the section Health

Share

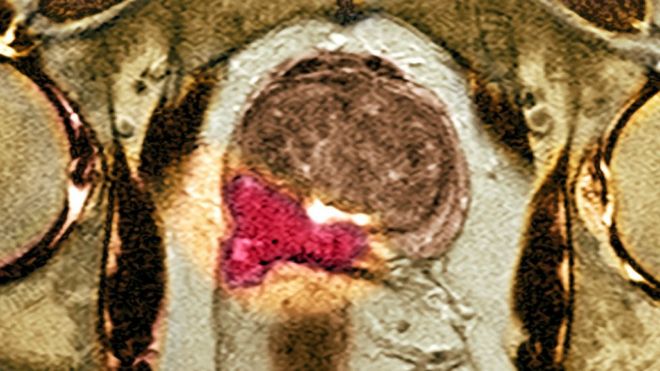

Image copyrightSPLImage captionScans of the prostate can show if there is a cancerous growth

Image copyrightSPLImage captionScans of the prostate can show if there is a cancerous growth

The biggest leap in diagnosing prostate cancer “in decades” has been made using new scanning equipment, say doctors and campaigners.

Using advanced MRI nearly doubles the number of aggressive tumours that are caught.

And the trial on 576 men, published in the Lancet, showed more than a quarter could be spared invasive biopsies, which can lead to severe side-effects.

The NHS is already reviewing whether the scans can be introduced widely.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in British men, and yet testing for it is far from perfect.

If men have high prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels in the blood, they go for a biopsy.

Twelve needles then take random samples from the whole of the prostate.

It can miss a cancer that is there, fail to spot whether it is aggressive, and cause side-effects including bleeding, serious infections and erectile dysfunction.

“Taking a random biopsy from the breast would not be accepted, but we accept that in prostate,” said Dr Hashim Ahmed, a consultant and one of the researchers.

Around 100,000 to 120,000 men go through this every year in the UK.

Scanning

The trial, at 11 hospitals in the UK, used multi-parametric MRI on men with high PSA levels.

It showed 27% of the men did not need a biopsy at all.

Media captionDr Hashim Ahmed describes on Radio 4’s Today a new breakthrough in prostate cancer diagnosis

And 93% of aggressive cancers were detected by using the MRI scan to guide the biopsy compared with just 48% when the biopsy was done at random.

Dr Ahmed, who works at University College London Hospitals, told the BBC News website: “This is a significant step-change in the way we diagnose prostate cancer.

“We have to look at the long-term survival, but in my opinion by improving the detection of important cancers that are currently missed we could see a considerable impact.

“But that will need to be evaluated in future studies, and we may have to wait 10 to 15 years.”

Chris, 70, from Hassocks, West Sussex

Chris first noticed the symptoms at the theatre a decade ago, when he needed to go to the toilet repeatedly.

Doctors found his prostate was enlarged.

In May last year, Chris needed to see his doctor again, as he was feeling tired a lot of the time.

Prostate cancer was suspected, and he was offered an MRI scan as part of the trial.

He says: “I’d heard from a friend that a prostate biopsy could be extremely painful and uncomfortable, so was pleased to know that I wouldn’t be sent for one unless the doctors were confident I needed it.”

In the end, he still needed a biopsy, and he was diagnosed with a cancer that had not spread out of the tumour.

He is now considering what to do about treatment.

Angela Culhane, the chief executive at Prostate Cancer UK, described the current system of testing as “notoriously imperfect”.

She added: “This is the biggest leap forward in prostate cancer diagnosis in decades.”

The study, led by the Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit, is already being considered by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

It will decide whether the NHS can afford multi-parametric MRI for prostate cancer.

Each scan costs between £350 and £450 pounds per patient – so introducing them for all patients across the UK would have a bill around the £40m mark.

But each biopsy costs the NHS £450 so reducing the number would deliver savings. Catching aggressive cancers earlier could also deliver savings as could not treating patients with very low-risk cancers.

A full cost-effectiveness analysis is being carried out.

Prof Ros Eeles, from the Institute of Cancer Research in London, said the study was “very important” and “provides ground breaking data”.

The chairman of the British Society of Urogenital Radiology, Dr Philip Haslam, said: “Today’s findings represent a huge leap forward in prostate cancer diagnosis.”

However, he warned the biggest issue could be the number of scanners and training people to interpret the results.