ACS Culprit Lesions: High-Risk Plaque Traits, Little Calcium

Marlene Busko

July 27, 2015

RELATED LINKS

ACS Patients on Statins Less Likely to Have High-Risk Plaque

ACS Patients on Statins Less Likely to Have High-Risk Plaque High-Risk Plaque Predicts ACS in ER Patients With Chest Pain

High-Risk Plaque Predicts ACS in ER Patients With Chest Pain Coronary CT in the ED Saves Time Screening for ACS

Coronary CT in the ED Saves Time Screening for ACS

My Alerts

Click the topic below to receive emails when new articles are available.

Add “Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS)”

RELATED DRUGS & DISEASES

Coronary Artery Calcification on CT Scanning

Imaging of Cardiac Calcifications

Clopidogrel Dosing and CYP2C19

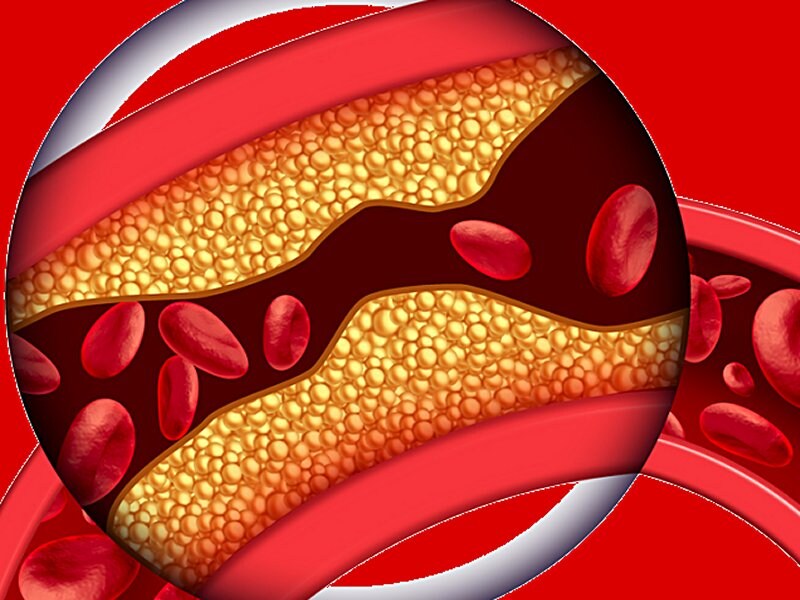

LAS VEGAS, NV — In patients who presented to the emergency room with chest pain and were found to have ACS, the culprit lesions had significant stenosis (>50%) and high-risk plaque features, but little calcification, in a new study[1].

Dr Maros Ferencik (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR and Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston) presented these findings from a secondary analysis of data from the Rule Out Myocardial Infarction With Computer Assisted Tomography II (ROMICAT II) trial, in an oral session at the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT) 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting.

“When you look at the [coronary artery] segment where something bad is happening, you realize there is stenosis, there are all these high-risk plaque features, but these are not the segments that have the highest amount of calcium,” Ferencik told heartwire from Medscape.

“I think this is going to be a very controversial terrain, depending on the population,” a member of the audience commented. “These data make perfect sense for an ACS population, but it may not be the case for other slices of the universe of patients with coronary atherosclerosis.”

Ferencik agreed, adding that “this is just a very small piece of the puzzle, but certainly a very interesting piece, I believe.”

Moreover, “all these acute-chest-pain patients are [about] 50, 55 years old [in ROMICAT II],” he noted. “Once you get to your 60s, mid-60s, and 70s you have a lot of [coronary artery] calcification, and this relationship [between culprit lesions and calcification] is probably different,” he speculated.

Are Culprit Lesions High in Calcium?

ROMICAT II showed that plaque with high-risk features—positive remodeling, low-attenuation [<30 Hounsfield units], napkin-ring sign, and spotty calcium—predicts which patients with acute chest pain have ACS, as previously published by Ferencik and colleagues[3] and reported by heartwire .

Increased coronary artery calcification correlates with increased plaque burden, but it may indicate an advanced stage of atherosclerosis that is not related to high-risk plaque. However, other research has also identified a “statin and coronary calcium paradox”—that is, while statins promote plaque regression, they also promote coronary atheroma calcification, which may explain how they stabilize plaque[3,4].

Ferencik and colleagues aimed to determine how significant coronary artery stenosis, high-risk plaque features, and calcium content in coronary artery segments are associated with culprit lesions in patients with ACS.

They analyzed data from 260 low- to intermediate-risk patients with acute chest pain and possible ACS who had been randomized to the coronary CT angiography (CCTA) arm of the ROMICAT II trial and also had CCTA scans that showed coronary plaque.

ACS, independently adjudicated, was seen in 37 patients. The culprit coronary lesions were identified by invasive angiography in 32 of these patients.

At baseline, patients with or without detected ACS had a similar mean age (56) and a similar prevalence of individual CV risk factors and number of CV risk factors, although there were fewer women in the ACS group (16% vs 40%).

Compared with patients without ACS, patients with ACS were more likely to have coronary arteries with >50% stenosis (78% vs 7%, P <0.001) and high-risk plaque features (95% vs 59%, P<0.001). Patients with ACS also had a higher total median Agatston CAC score: 229 (interquartile range [IQR] 75–517) vs 27 (IQR 0–99) (P<0.001).

The 207 total coronary artery segments were divided into tertiles based on their calcification, which showed that the prevalence of high-risk plaque was greater in the coronary artery segments with the least calcification.

The researchers compared the 41 culprit segments vs the 200 nonculprit segments (in the 37 patients who had ACS), which showed that culprit segments were more likely to have >50% stenosis (81% vs 11%, P<0.001) and high-risk plaque (76% vs 51%, P=0.005).

However, the median CAC scores were similar in nonculprit and culprit lesions: 22 (IQR 4–71) vs 14 IQR (0–51), respectively (P=0.372).

In a regression model that adjusted for the fact that multiple measurements came from the same patient, >50% stenosis and the presence of high-risk plaque, but not CAC score, were significant predictors of a culprit lesion.

Predictors of Culprit Lesions in Patients with ACS

| Predictor | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P |

| >50% stenosis | 40.2 (15.6–103.9) | <0.001 |

| High-risk plaque | 3.4 (1.3–9.1) | 0.02 |

| Segment CAC score | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.47 |

Ferencik cautioned that the analysis wasn’t prospectively defined, the culprit lesions were detected retrospectively, and radiographic angiograms were available for only 32 patients.

Nevertheless, “our findings suggest that local advanced calcification actually may represent a more stable stage of atherosclerosis, while culprit lesions are characterized by smaller amounts of CAC and the presence of high-risk features,” he concluded.

Ferencik has no relevant financial relationships.