Unseen Cost of Weight Loss and Aging: Tackling Sarcopenia

Losses of muscle and strength are inescapable effects of the aging process. Left unchecked, these progressive losses will start to impair physical function.

Once a certain level of impairment occurs, an individual can be diagnosed with sarcopenia, which comes from the Greek words “sarco” (flesh) and “penia” (poverty). Individuals with sarcopenia have a significant increase in the risk for falls and death, as well as diminished quality of life.

Muscle mass losses generally occur with weight loss, and the increasing use of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) medications may lead to greater incidence and prevalence of sarcopenia in the years to come.

A recent meta-analysis of 56 studies (mean participant age, 50 years) found a twofold greater risk for mortality in those with sarcopenia vs those without. Despite its health consequences, sarcopenia tends to be underdiagnosed and, consequently, undertreated at a population and individual level. Part of the reason probably stems from the lack of health insurance reimbursement for individual clinicians and hospital systems to perform sarcopenia screening assessments.

In aging and obesity, it appears justified to include and emphasize a recommendation for sarcopenia screening in medical society guidelines; however, individual patients and clinicians do not need to wait for updated guidelines to implement sarcopenia screening, treatment, and prevention strategies in their own lives and/or clinical practice.

Simple Prevention and Treatment Strategy

Much can be done to help prevent sarcopenia. The primary strategy, unsurprisingly, is engaging in frequent strength training. But that doesn’t mean hours in the gym every week.

With just one session per week over 10 weeks, lean body mass (LBM), a common proxy for muscle mass, increased by 0.33 kg, according to a study which evaluated LBM improvements across different strength training frequencies. Adding a second weekly session was significantly better. In the twice-weekly group, LBM increased by 1.4 kg over 10 weeks, resulting in an increase in LBM more than four times greater than the once-a-week group. (There was no greater improvement in LBM by adding a third weekly session vs two weekly sessions.)

Although that particular study didn’t identify greater benefit at 3x/week compared with 2x/week, the specific training routines and lack of a protein consumption assessment may have played a role in that finding.

Underlying the diminishing benefits, a different study found a marginally greater benefit in favor of performing ≥ 5 sets per major muscle group per week compared with < 5 sets per week for increasing muscle in the legs, arms, back, chest, and shoulders.

A previous commentary outlined an overall approach to preventing loss of muscle mass while taking GLP-1–related medications. Of note, a diet with sufficient protein is critical for optimizing muscle mass gains as part of regular strength-training routines. One study performed in older adults with frailty found an average loss of 0.25 kg of LBM with consumption of 1.0 grams of protein per kilogram of total body weight per day (g/kg/d) despite 2 days of strength training per week for 24 weeks. In that same study, consuming 1.3 g/kg/d of protein led to an average increase of 1.25 kg of LBM during the same period and in association with the same strength-training routine as those consuming 1.0 g/kg/d. Meta-analyses performed to assess an amount of protein to provide optimal benefit to strength and muscle for strength-training individuals determined those amounts to be 1.5 g/kg/d and 1.62 g/kg/d, respectively. While historically a low-protein diet was recommended to prevent disease progression in individuals with chronic kidney disease(CKD), a recent study found reduced risk for death in patients with CKD with greater reported protein consumption. A separate study, using a mendelian randomization methodology, found a similar reduction in mortality risk among individuals with CKD who consumed greater amounts of protein.

Patients in Need of Sarcopenia Assessments

Although a gradual loss of muscle mass occurs over the course of life, sharp declines can also occur following an illness or an injury involving long bedrest. For example, one studyfound that 5 days of limb immobilization led to a 1.5% loss of quadriceps volume, equivalent to an amount of muscle loss, that, when extrapolated to the full body, may require 10 weeks of strength training twice weekly to regain.

In weight loss, such as from GLP-1–related medications, the sarcopenia risk may accrue long term, as it does in aging. Individuals who lose weight using GLP-1s may experienceimproved physical function in the short term (a little over a year), despite 20%-40% of the total weight lost coming from muscle mass; however, this loss of muscle may cause limitations over time.

If someone lost 20 lb of their total body weight through the use of semaglutide and was not strength training and not consuming enough protein, the amount of LBM lost (assuming 40% of total weight lost) is 8 lb or 3.62 kg. If a body-composition assessment was not performed before and after the weight loss, it won’t be possible to estimate how much of the lost weight is coming from muscle compared with fat. This individual may not yet experience a loss in strength as a result of that muscle loss, particularly if they are in their 50s; however, a person in their 70s is more likely to experience some degree of limitation in their physical function as a result.

For some individuals, that amount of muscle mass reduction can tip them into the sarcopenic range, which increases the risk for hip fractures. Sarcopenia contributed to 71% of hip fractures in one community-level study. Hip fractures are not uncommon. One studyreported a lifetime risk for a hip fracture of 16%-18% in White women of and 5%-6% in White men. Furthermore, 34% of older adult patients who suffer a hip fracture die within 1 year of the fracture, and of those who survive, many experience impaired mobility and quality of life even up to 2 years afterward.

To outline an unfortunate but possible trajectory, an individual could unknowingly lose muscle in association with weight loss achieved in their 50s, acquire a mild case of pneumonia at a social event in their 60s or 70s, end up in the hospital for 7 days undergoing treatment for pneumonia, experience a rapid loss of muscle mass during the hospitalization, leave the hospital after completing pneumonia treatment, only to then fall ascending the stairs to their home, suffer a hip fracture, and end up back in the hospital.

How Do Busy Clinicians Fit In Sarcopenia Screening?

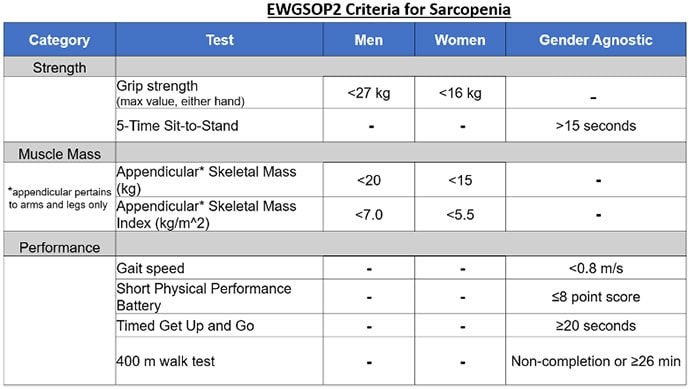

Different sarcopenia-related societies have proposed different criteria and thresholds for diagnosis. Of these different guidelines, those from the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) are the most recent and are summarized below:

EWGSOP-defined sarcopenia categories:

- One criterion met = Probable sarcopenia

- Two criteria met = Sarcopenia

- Three or more criteria met = Severe sarcopenia

An assessment for sarcopenia does not require excessive time, cost, or safety risk. Of the tests included for screening for sarcopenia in the EWGSOP criteria, grip strength and the 5-Time Sit-to-Stand (5tStSt) assessments are probably the most feasible to perform in clinic. These are evidence-based and can be performed together in about 2 minutes total time.

Hand Grip Strength

The clinically validated Jamar Hydraulic Hand Dynamometer is available for about $270, but devices priced at $30 are probably reasonably accurate and worthy of consideration for clinics with budgetary limitations. To perform the grip strength test, the patient simply squeezes the device with as much force as they can, once with each hand. The device will display the max force generated with each squeeze.

5-Time Sit Stand to Test

For the 5tStSt, the patient should begin in a seated position, cross their arms over their shoulders (so that their hands are not used to assist in the movement), and rise to a full stand before returning to a seated position. This motion should be completed five times, and the patient should be instructed to complete the five repetitions as quickly as possible, while the time required to complete the five repetitions is recorded.

Ideally, if performed during a clinic visit, the clinicians would show the patient how their results compare with demographic norms for each test; see here for examples of demographic norms for grip strength and here for the 5tStSt.

Body Composition Assessments

Body composition data are also included as part of a sarcopenia assessment and have gender-specific thresholds defined in the EWGSOP criteria. A body composition assessment provides data on LBM (which is a proxy for muscle mass) and fat mass. A recent study demonstrated that percent body fat provides greater sensitivity than body mass index for diagnosing obesity and metabolic syndrome.

When to Consider Sarcopenia Screening

An extensive body of evidence on sarcopenia supports sarcopenia screening for all patients older than age 65. Given the risk for muscle mass reductions that occur with weight loss in general and GLP-1–related medications more specifically, sarcopenia screening is probably appropriate for certain patients younger than 65 years as well.

Clinical judgement should be used to determine when and whom to assess for sarcopenia; however, given that the screening assessments are fast, safe, and have minimal cost, a low threshold for screening appears appropriate. For example, even for a 50-year-old patient who has not been physically active, sarcopenia assessments may indicate below-average performances, and this knowledge can serve as motivation for this patient to adopt an exercise regimen to address strength-related limitations that have already begun to manifest. Further, keeping a record of screenings performed in younger years can serve as points of comparison for repeat assessments later on.

Self-Directed Sarcopenia Screening

Some healthcare providers may not be familiar with the diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia; efforts to promote greater awareness and testing should continue. That said, patients can perform some of the testing themselves if so desired.

The 5tStSt, 400-meter walk test, and Timed Get Up and Go (TUG) tests do not require a clinician. The 400-meter walk test simply evaluates the time required for completion of walking this distance. The TUG test evaluates the time required for a patient to rise from a chair and then walk 3 meters forward. As part of the TUG test, patients can use their arms to assist in rising from the chair.

It has been said that every job has a “sales” component. This is also true of medicine. Doctors must “sell” patients on an explanation for their symptoms and must elicit “buy-in” from them on a treatment plan for it to be most effective. Data from sarcopenia assessments can increase the power of the sales pitch aimed at motivating patients to adopt and/or improve an exercise routine.